Behind Ávila’s medieval walls, among the best-preserved in Europe, lies a story that transformed Jewish spirituality. Beyond its natural and architectural beauty, this UNESCO World Heritage city offers a different reading: streets that were once home to one of Castile’s most influential Jewish communities and the life of a singular figure, Moshe ben Sem Tob de León, the man credited with writing the Zohar, the foundational text of Kabbalah.

Just over an hour from Madrid, Ávila is known for its walls, its churches, and the legacy of Saint Teresa. What few visitors realize is that the city holds a deep Sephardic heritage, now brought back to light thanks to the Jewish Heritage Network (Red de Juderías – Caminos de Sefarad), which has developed routes, interpretive panels, and cultural activities to make this memory accessible.

Jewish presence in Ávila dates back to the twelfth century. By the late Middle Ages, its aljama was among the most important in Castile, with synagogues, ritual baths, and a cemetery that today survives as the Garden of Sefarad. At its peak, Jews represented nearly twenty percent of the population, engaged in trade, crafts, and finance.

It was in this context, around 1295, that Moshe de León arrived in the city. Born in León around 1240, he was a philosopher, mystic, and prolific writer. Before settling in Ávila, he traveled through major Jewish quarters such as Guadalajara and Valladolid, and in 1264 commissioned a copy of Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed, evidence of his early interest in philosophy. But his most celebrated work would be another: the Zohar, the “Book of Splendor.”

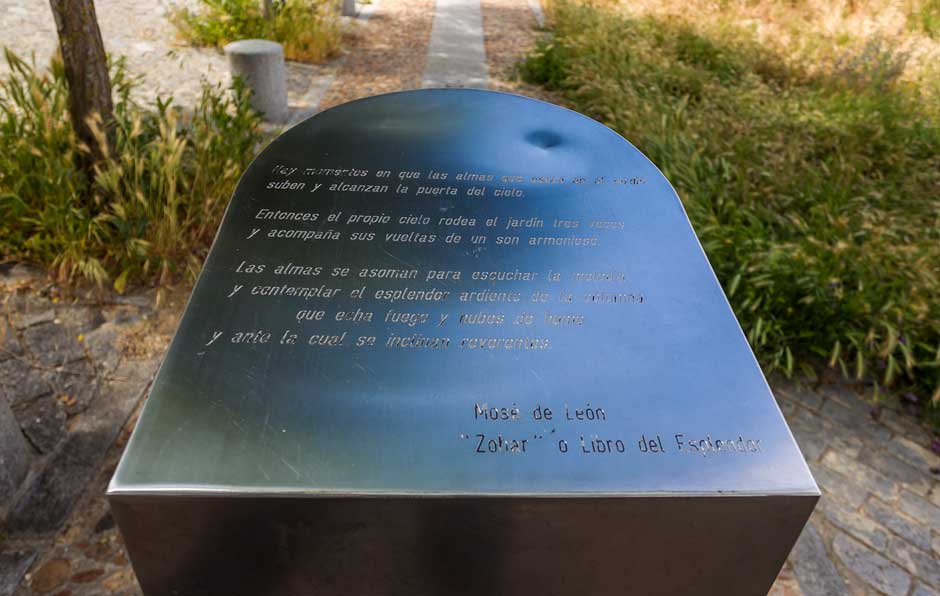

Moshe’s intellectual path reflects the tensions within Judaism at the time, divided between two currents: the orthodox literalists, backed by elites and defenders of strict law, and the mystics, who preached poverty and communion with nature, closer to popular classes. Moshe aligned with the mystics. His itinerant life had an almost apostolic dimension: spreading ideas, writing, debating. In Ávila, he found calm in the house of Yuçaf de Ávila, an influential Jew who offered support and comfort. There, Moshe completed the Zohar—a book written in Aramaic to appear ancient, structured as dialogues and commentaries attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. The debate over its sole authorship, however, remains open.

Moshe’s intellectual path reflects the tensions within Judaism at the time, divided between two currents: the orthodox literalists, backed by elites and defenders of strict law, and the mystics, who preached poverty and communion with nature, closer to popular classes. Moshe aligned with the mystics. His itinerant life had an almost apostolic dimension: spreading ideas, writing, debating. In Ávila, he found calm in the house of Yuçaf de Ávila, an influential Jew who offered support and comfort. There, Moshe completed the Zohar—a book written in Aramaic to appear ancient, structured as dialogues and commentaries attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. The debate over its sole authorship, however, remains open.

Beyond the Zohar, Moshe wrote about twenty-five works, including Sefer ha-Rimmon (1287), a mystical interpretation of ritual laws; Ha-Nefesh ha-Hakamah (1290), on the soul and cosmic restoration; Shekel ha-Kodesh (1292), reflections on life after death; and Sefer ha-Sodot (1293), on divine mysteries.

He died in 1305 in Arévalo, during a journey to meet another theologian. He was buried in Ávila’s Jewish cemetery, rediscovered in 2012 and now memorialized as the Garden of Sefarad, the largest Jewish necropolis found in Spain.

Walking Ávila Today

The Jewish route through Ávila also bears Moshe de León’s imprint. It begins at Calle Santo Domingo, the heart of the old Jewish quarter, and continues along Vallespín and Reyes Católicos, where interpretive panels mark historic homes. The Garden of Moshe de León, near the Puerta de la Malaventura, honors the author of the Zohar. The Garden of Sefarad, on the outskirts, recalls those who rested there for centuries. Nearby, the Mosén Rubí Chapel and the church of Nuestra Señora de las Nieves rise over former synagogues—silent witnesses to adaptation and rupture.

Ávila also preserves the only surviving copy of the 1492 Edict of Expulsion in Castile, a document that marked the end of coexistence.

Ávila also preserves the only surviving copy of the 1492 Edict of Expulsion in Castile, a document that marked the end of coexistence.

Each September, the city joins the European Days of Jewish Culture, with guided tours, concerts, and culinary workshops that reinterpret Sephardic recipes using local ingredients. This is not just about looking at stones—it is a dialogue between past and present, a story that continues to unfold.