In Béjar, perched on the slopes of the Sierra de Salamanca, a museum serves as a key to memory and a starting point for understanding a city that for centuries was home to a thriving Jewish community. The David Melul Jewish Museum is not merely a hall of ancient artifacts; it is a layered narrative that guides visitors from medieval coexistence to the Sephardic diaspora and invites them to explore the city with fresh eyes.

Housed in a fifteenth-century manor and opened in 2004 thanks to the philanthropic vision of David Melul, the museum unfolds across three floors that connect local history with the broader story of Sefarad.

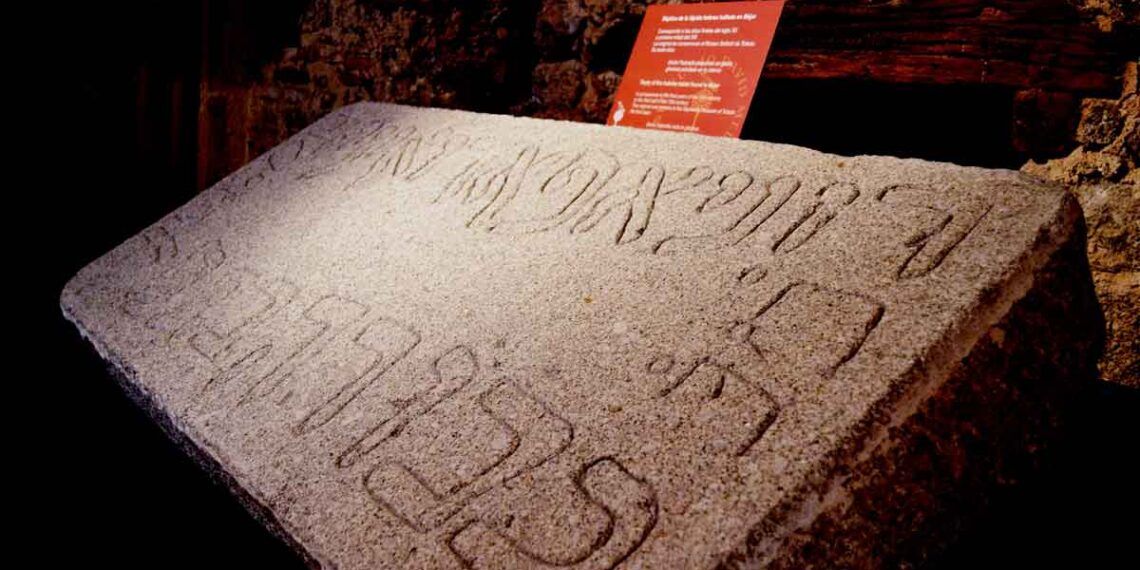

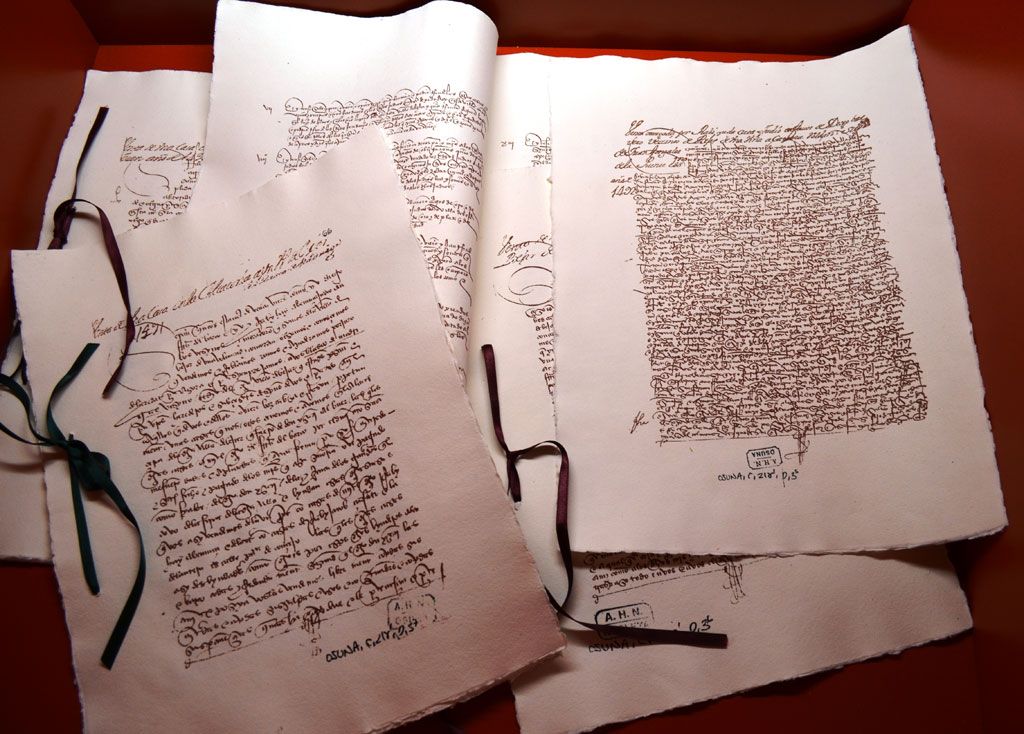

The visit begins with a map tracing Jewish presence in Spain and in Béjar, documented since the late twelfth century. Among the highlights are the Fuero of Béjar, which regulated life among Christians, Muslims, and Jews, and ritual objects such as the menorah, tallit, and tefillin, tangible reminders of practices lost after 1492. An audiovisual presentation on the Edict of Granada sets the date and context of the rupture, while the first floor focuses on the era of the conversos, displaying inquisitorial documents and a scale model of fifteenth-century Béjar that situates the Jewish quarter near the Ducal Palace and the churches of Santa María, San Gil, and San Juan.

The top floor opens onto the geography of exile: Mediterranean and Atlantic routes, the Judeo-Spanish language, and testimonies from families who preserved their link to the city through the surname Béjar and its variants.

Yet the museum does not exhaust the story. Béjar was once a flourishing aljama, with its own synagogue, school, ritual baths, butcher shop, oven, hospital, and cemetery. Its Jews worked in trade, crafts, and medicine. Among its notable figures was Rabbi Hayyim ibn Mussa, physician, translator, and poet, author of Magen va-Romav, a work that reflects the intellectual vitality of the community. Other names such as Samuel de la Tetilla and Simuel de Medina appear in records as tax collectors and artisans, part of the fabric of daily life. All this unfolded under the protection—and at times the pressure—of the Zúñiga family, lords of Béjar, who ruled from the Ducal Palace.

Yet the museum does not exhaust the story. Béjar was once a flourishing aljama, with its own synagogue, school, ritual baths, butcher shop, oven, hospital, and cemetery. Its Jews worked in trade, crafts, and medicine. Among its notable figures was Rabbi Hayyim ibn Mussa, physician, translator, and poet, author of Magen va-Romav, a work that reflects the intellectual vitality of the community. Other names such as Samuel de la Tetilla and Simuel de Medina appear in records as tax collectors and artisans, part of the fabric of daily life. All this unfolded under the protection—and at times the pressure—of the Zúñiga family, lords of Béjar, who ruled from the Ducal Palace.

Today, travelers can walk through these settings. The David Melul Jewish Museum is the starting point, but the experience extends into the streets. The old Jewish quarter lie around Calle Mayor and the vicinity of the Ducal Palace. There, among stately homes and churches, the coexistence that the Fuero sought to regulate once took shape. Nearby, the Renaissance garden of El Bosque, with its ponds and pathways, becomes each summer a stage for Sephardic concerts, where music revives echoes of a past that seemed lost. The Plaza Mayor and historic churches complete a route that blends art, history, and memory.

Curiously, Béjar’s story still resonates in thousands of people around the world, part of the Sephardic diaspora. With the expulsion from Spain and subsequent migrations, Jews and conversos carried the city’s name far beyond the mountains. Today, entire families bear surnames such as Béjar, Behar, Bejarano, or Becerano, all derived from the original toponym. These names traveled across the Mediterranean and the Americas, adapting to different alphabets and pronunciations yet preserving the reference to the city as a symbol of identity.

Curiously, Béjar’s story still resonates in thousands of people around the world, part of the Sephardic diaspora. With the expulsion from Spain and subsequent migrations, Jews and conversos carried the city’s name far beyond the mountains. Today, entire families bear surnames such as Béjar, Behar, Bejarano, or Becerano, all derived from the original toponym. These names traveled across the Mediterranean and the Americas, adapting to different alphabets and pronunciations yet preserving the reference to the city as a symbol of identity.

Among their descendants are figures such as the rabbi and intellectual Haim Bejarano, a staunch defender of Judeo-Spanish culture; anthropologist Ruth Behar, an authority on Sephardic memory; businessman Howard Behar, former president of Starbucks; and musician Dan Bejar, a recognized voice in the indie scene. The museum holds photographs and testimonies sent from Seattle, London, Sofia, and Tel Aviv, weaving an emotional network that restores Béjar to its global dimension.

The connection between Béjar and its Sephardic heritage is also reinforced through cultural programming. Each September, the city joins the European Days of Jewish Culture with guided tours, concerts, and workshops that reinterpret Sephardic recipes using local ingredients. In summer, El Bosque becomes a stage for music that revives Mediterranean repertoires, and in autumn, the hiking event known as La Salamanquesa retraces the path of exile through the mountains. These activities transform history into living culture, offering visitors an experience that combines heritage and nature.